[Epistemic status is that if anyone quoted here disputes the way they are portrayed, I will probably just accept that by default. My aim is not to strawman, it’s to at least portray people correctly so that they can respond with, “you understood me, and you’re wrong.”]

There’s a tendency among writers in the rationality sphere to discuss social dynamics in what I claim is a fairly negative way. I call this tendency “reality criticism.” Most people are not infinitely pessimistic, but I will argue throughout this piece, showing examples where I can, of where I believe it crosses ‘a line’ (which I attempt to gesture at, as yet not formally enough), or where it at least implies that other things are true which do cross the line.

(An important example I leave out is Inadequate Equilibria, which I may save for part two, if I choose to do a part two.)

Reddit, on Moloch:

I feel like I can never be optimistic again because of the dynamics described in it and the nature of competition. The most evil, dominant, violent organization eventually wins, forcing everyone else to be the same to compete with them. Humanity is fated to become the human equivalent of competing grey goo if it spreads throughout the solar system.

The top comment recommends The Goddess of Everything Else as the standard prescription for this. It is so named because it is supposed to explain why anything good exists at all. But it does not attempt to explain why anything good exists, it just acts as a poetic placeholder metaphor - “a god[dess] of the gaps”, if you will.

I have often been confused about this, because I don’t experience reality this poorly as a baseline, at least not poorly enough for me to make this my prior. I don't disvalue smokestacks this much. They might not be the prettiest things around, but they are, and were, a sign of industrial and economic progress.

As that comment said, everything must add up to “normality.” But Allen Ginsburg saw filth and ugliness. That’s what constituted his normality, so he wrote about it.

Moloch is introduced as the answer to a question – C. S. Lewis’ question in Hierarchy Of Philosophers – what does it? Earth could be fair, and all men glad and wise. Instead we have prisons, smokestacks, asylums. What sphinx of cement and aluminum breaks open their skulls and eats up their imagination?

Moloch certainly has to be based on someone's value-appraisal of an observation. Someone observes something they disvalue - like smokestacks and prisons - and wants an explanation that feels equally malignant. I don’t want to be interpreted as claiming these things aren’t bad at all. Just that they aren’t necessarily innately bad.

I am going to begin by taking note of this harder problem - one of value discernment - and then make it easier by moving to things we can agree about value on.

Like all good mystical experiences, it happened in Vegas. I was standing on top of one of their many tall buildings, looking down at the city below, all lit up in the dark. If you’ve never been to Vegas, it is really impressive. Skyscrapers and lights in every variety strange and beautiful all clustered together. And I had two thoughts, crystal clear:

It is glorious that we can create something like this.

It is shameful that we did.

I like Vegas. I like the look and feel of it, and I even kind of like the fact that it sort of condones certain “naughty” behaviors. It’s not a place everyone is meant to be at all times, except the people who work there (who probably don’t get to have fun most of the time).

That’s the harder problem.

I call it the harder problem because - although it is possible we have a value disagreement because we actually disagree about the facts - if you say “I like it” and I say “I don’t like it”, it is possible that this is simply true and also does not decompose any further. We are “orthogonal”, you might say. A value disagreement can therefore act as a conversation stopper, and that’s unfortunate. I have hopes that we can actually dissolve the disagreement.

Pause and think about this for a moment: If you and I have a value disagreement (or at least believe that we do), of substantial enough degree that the trajectory of the world looks quite different in value terms to us, don’t you think we might feel different levels of desire to explain why there seems to be more good versus bad in the world?

However, human beings are probably not that mutually orthogonal.

I think it ought to be mentioned that in the context of AI, and in particular the rationality community - which I hope to one day stop talking about so much, but cannot avoid for now - the idea that civilizations tend to fail to align such technology to themselves means there is a problem with “reality”, in that group utility and individual utility, as a rule, tend not to align, and create malignant dynamics.

This is what I call “reality criticism.”

What counts as true cynicism? I’d argue that it’s reality-critiquing, and that system-critiquing is not cynical. I.e., “maybe your system failed because it’s broken, and not because all of reality conspired to make a good thing lose and a bad thing win” is not cynicism.

It requires belief both that humans are mostly self-interested actors, but also that this feature goes against what is required to build a stable, functioning society. There needs to be systematic, emergent features that are diametrically opposed to each other. These are usually framed as the wants of society versus the wants of the individual. And, for it to be pessimistic cynicism, it also has to posit that these forces either lead to destruction or to a state of quasi-permanent malignance, such as suffering and strife.

One would naturally be inclined to look at the case of evolution. Humans evolved to be the way they are, so if we evolved to be self-interested actors, that implies that being a self-interested actor is what “works.” Humans evolved to be some combination of self-interested and altruistic, of course. Human intelligence is also the most recent iteration of intelligence that we know of to have evolved (so this is excluding AI, for now). It seems trivial to infer that if some kind of malignant forces which were opposed to, and stronger than, “goddess of everything else” forces, that we would see more examples of smart things, possibly smarter than human things, going extinct more frequently.

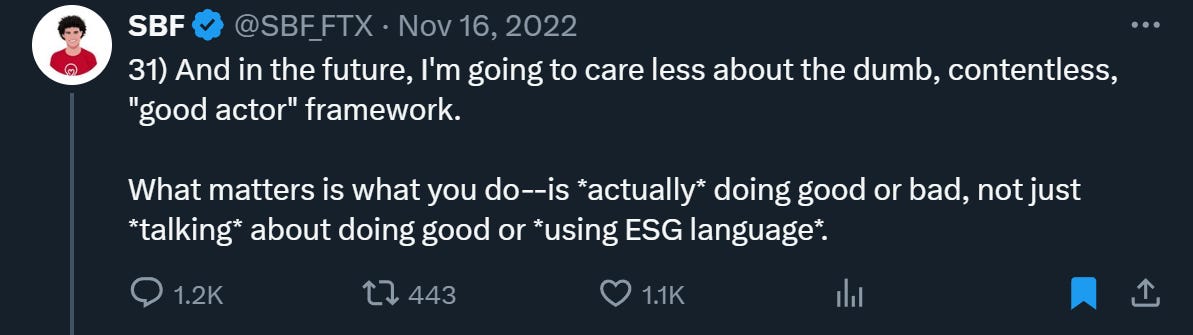

There are also other variations of cynicism. One particular type we will be examining has to do mainly with communications (e.g. memetics). This variant posits that society tends to converge towards a "post-truthian" state.

Concrete examples of this state are actually somewhat sparse, and often localized to specific failures. It is mostly defined in terms of the abstract dynamic that is theorized to produce it. These narratives became especially popular during the first Trump administration, again during COVID-19, and again during the rise of advanced AI, to name specific recent times.

This type of cynicism, because it itself is a socially-constructed narrative, is of particular interest to me, because one would be immediately inclined to ask why we can't have a more optimistic or pro-social "post-truthian" narrative.1

Social Commentary Examples From Rationality

Examples From Immoral Mazes (Zvi Mowshowitz)

I warn you that this section will have lots of block quotes. Like the following, which is a summary of what Immoral Mazes is about:

The Immoral Mazes sequence is an exploration of what causes that hell, and how and why it has spread so widely in our society. Its thesis is that this is the result of a vicious cycle arising from competitive pressures among those competing for their own organizational advancement. Over time, those who focus more on and more value such competitions win them, gain power and further spread their values, unless they are actively and continuously opposed.

Immoral Mazes is somewhat like a theory of “aging” for organizations. It describes how organizations are born and die, and especially why they die. Zvi agrees that society continues to have nice things at all because organizations die and are replaced by better ones, in an evolutionary process.

But he also says:

Our institutions of all kinds are becoming increasingly dysfunctional, increasingly concerned with politics in its broad sense, and incapable of useful action. Thus, people increasingly have the instinct that Moloch inevitably wins everywhere. We are disarming the forces that keep Moloch in check.

His thesis is that while the whole economy has imperfect competition, organizations internally have perfect competition or even “super-perfect competition” which makes the net gain from optimization no higher than break-even for any of the participants. Middle-managers in the hierarchy are forced to act in increasingly immoral ways if they wish to be successful.

He believes mazes are more of a problem now than they were in the past, and has several proposed reasons for why this is.

What has made these mazes so much more powerful than in the past?

Some factors are real and inevitable. We need more large organizations for our civilization to function, than did prior civilizations, and in many ways they get to better leverage big data. machine learning and the internet, giving them an edge. As we grow safer and wealthier, our demand for the illusion of security rises, and mazes are relatively better positioned to provide that illusion.

So there is a bit in here about our society innately needing more of a thing that is entangled with badness (large organizations), and also more information and better capabilities leading to negative consequences (machine learning and big data). There is also the idea that as society becomes safer and wealthier, it begins to demand the illusion of even more safety, which ends up causing bad things. Each of these reasons relies on some kind of “good X” entangled with a “bad Y”, where both increase at the same time.

The machine learning / big data reason is particularly curious, because it posits no more than technological progress exacerbating maze-like dynamics. This is presumably because it increases the incentive to Goodhart metrics, enables greater surveillance (and thus more hierarchy, which is bad), and adds more complexity than it reduces. Instead of discussing why I believe there is reason to doubt this, I think it is preferable to look more at the major, theoretical reasons which should suffice to cover this instance as well.

He uses Alexander’s Moloch metaphor as a starting place for the theory. So let’s look at his / Alexander’s presentation of it.

From Moloch Hasn’t Won (my snarky comments in bold):

Consider Scott Alexander’s Meditations on Moloch. I will summarize here.

Therein lie fourteen scenarios where participants can be caught in bad equilibria.

In an iterated prisoner’s dilemma, two players keep playing defect. [Do they??]

In a dollar auction, participants massively overpay. [If they are stupid.]

A group of fisherman fail to coordinate on using filters that efficiently benefit the group, because they can’t punish those who don’t profit by not using the filters. [And yet we have fish.]

Rats are caught in a permanent Malthusian trap where only those who do nothing but compete and consume survive. All others are outcompeted. [How is this different from other organisms?]

Capitalists serve a perfectly competitive market, and cannot pay a living wage. [May wanna check with Tyler Cowen on this.]

The tying of all good schools to ownership of land causes families to work two jobs whose incomes are then captured by the owners of land. [Marxism.]

Farmers outcompeted foragers despite this perhaps making everyone’s life worse for the first few thousand years. [How do we know this?]

Si Vis Pacem, Para Bellum: If you want peace, prepare for war. So we do. [This doesn’t not make sense to do.]

Cancer cells focus on replication, multiply and kill off the host. [Not everyone dies of cancer.]

Local governments compete to become more competitive and offer bigger bribes of money and easy regulation in order to lure businesses. [This may happen, sure?]

Our education system is a giant signaling competition for prestige. [Yes, but does this mean your education is worthless?]

Science doesn’t follow proper statistical and other research procedures, resulting in findings that mostly aren’t real. [Replication crisis doesn’t affect the whole of Science, nor is it necessarily a permanent state of affairs.]

Governments hand out massive corporate welfare. [They do, but some policy makers maybe disagree with this, so this example is too small.]

Have you seen Congress? [What does this mean?]

Later, I am going to examine a few of those bullet-points more in-depth.

Here’s even more reality-critique:

The optimizing things will keep getting better at optimizing, thus wiping out all value. When we optimize for X but are indifferent to Y, we by default actively optimize against Y, for all Y that would make any claims to resources. Any Y we value is making a claim to resources. See The Hidden Complexity of Wishes. We only don’t optimize against Y if either we compensate by intentionally also optimizing for Y, or if X and Y have a relationship (causal, correlational or otherwise) where we happen to not want to optimize against Y, and we figure this out rather than fall victim to Goodhart’s Law.

The greater the optimization power we put behind X, the more pressure we put upon Y. Eventually, under sufficient pressure, any given Y is likely doomed. Since Value is Fragile, some necessary Y is eventually sacrificed, and all value gets destroyed.

This quote is ostensibly for the purpose of making us more cautious. But using the phrase, “wiping out all value”, makes us wonder how much this is to be taken literally versus hyperbolically. The Hidden Complexity of Wishes is not being hyperbolic.

But we are always going to get the optimization target a little bit wrong. There is always going to be some Y that we are accidentally indifferent to when we optimize for an X. Once we do this, we observe that things are worse, or not as good as we expected. Then, adjusting our models, we discover that we needed to optimize for X + Y (or some new variable that incorporates both in some way). This is a rinse-and-repeat process, which only fails when the degree of error is large enough to end this process.

I actually expect that cynics are forced to be somewhat inconsistent, in that they cannot claim that the world will go to shit no matter what we do (see my earliest points). But they may claim that there are inherent forces of darkness and evil that we have to fight against at all times.

Of course, there really are "doomers" out there, who believe that we probably will go extinct.

From Perfect Competition:

In Meditations on Moloch, Scott points out that perfect competition destroys all value beyond the axis of competition.

Which, for any compactly defined axis of competition we know about, destroys all value.

This is mathematically true.

Yet value remains.

Thus competition is imperfect.

(Unjustified-at-least-for-now note: Competition is good and necessary. Robust imperfect competition, including evolution, creates all value. Citation/proof not provided due to scope concerns but can stop to expand upon this more if it seems important to do so. Hopefully this will become clear naturally over course of sequence and/or proof seems obvious once considered.)

Perfect competition hasn’t destroyed all value. Fully perfect competition is a useful toy model. But it isn’t an actual thing.

"Perfect competition" is quite similar to a static equilibrium a la Moloch.

This is a lot of where the ‘Moloch wins because essentially perfect competition’ intuitions originate. Take a system. In that system, assume that underlying conditions are permanently static, except for the participants. Assume the participants won’t meaningfully coordinate. Assume that participants who do better beat out those who do worse and expand and/or replicate and/or survive marginally better.

Yes. And so the question is how much the real world looks like this.

If the system says "punish people who deviate from the system", we regard this as a bad system. Reality says that such a system is a bad system which ought to be critiqued. Because reality is ultimately the cause of everything, it is the cause of this system existing temporarily too, but it is also the cause of us seeing it as a bad system, because it leads to poor outcomes.

We can accept that such systems could be self-reinforcing beyond a certain threshold. This should lead to particular establishments collapsing, though not all of society.

In fact - as libertarian economists often argue - bad firms going out of business is a good thing.

Abram Demski noticed a confusion:

I'm somewhat suspicious of this explanation, because in a culture where non-maze opportunities are opening up more and more, it seems like mazes should die. I think people's behavior is more dependent on context than it is on these subtle cultural influences, so I expect to see larger effect sizes from incentive structures changing than from negative cultures slowly festering over time. But perhaps it's a factor.

I want to take a closer look at the "fish pollution problem" from Meditations, which Scott says is "I feel like this is the core of my objection to libertarianism." It seems isomorphic to N-player prisoner's dilemma, as far as I know:

As a thought experiment, let’s consider aquaculture (fish farming) in a lake. Imagine a lake with a thousand identical fish farms owned by a thousand competing companies. Each fish farm earns a profit of $1000/month. For a while, all is well.

But each fish farm produces waste, which fouls the water in the lake. Let’s say each fish farm produces enough pollution to lower productivity in the lake by $1/month.

A thousand fish farms produce enough waste to lower productivity by $1000/month, meaning none of the fish farms are making any money. Capitalism to the rescue: someone invents a complex filtering system that removes waste products. It costs $300/month to operate. All fish farms voluntarily install it, the pollution ends, and the fish farms are now making a profit of $700/month – still a respectable sum.

But one farmer (let’s call him Steve) gets tired of spending the money to operate his filter. Now one fish farm worth of waste is polluting the lake, lowering productivity by $1. Steve earns $999 profit, and everyone else earns $699 profit.

Everyone else sees Steve is much more profitable than they are, because he’s not spending the maintenance costs on his filter. They disconnect their filters too.

Once four hundred people disconnect their filters, Steve is earning $600/month – less than he would be if he and everyone else had kept their filters on! And the poor virtuous filter users are only making $300. Steve goes around to everyone, saying “Wait! We all need to make a voluntary pact to use filters! Otherwise, everyone’s productivity goes down.”

Everyone agrees with him, and they all sign the Filter Pact, except one person who is sort of a jerk. Let’s call him Mike. Now everyone is back using filters again, except Mike. Mike earns $999/month, and everyone else earns $699/month. Slowly, people start thinking they too should be getting big bucks like Mike, and disconnect their filter for $300 extra profit…

A self-interested person never has any incentive to use a filter. A self-interested person has some incentive to sign a pact to make everyone use a filter, but in many cases has a stronger incentive to wait for everyone else to sign such a pact but opt out himself. This can lead to an undesirable equilibrium in which no one will sign such a pact.

We know that in evolutionary simulations of prisoner’s dilemma, strategies emerge such as tit-for-tat and win-stay, lose-shift that result in stable cooperation if these strategies are shared. (Presumably, in an evolutionary environment, these come to win out in large populations).

N-player Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma has recently been shown to bore out some cooperation.

Let’s take a look at Prisoner’s Dilemma in more detail ourselves.

Here’s the definition (for two players):

T = defector payoff

R = both cooperate

P = both defect

S = only you cooperate

2R > T + S (sum of cooperate is highest)

Here are some made-up N=2 and N=3 scenarios, modifying how much pollution is generated.

Let's say N = 2 and pollution = $200 to both, filter = $300:

T = $800 C D

R = $700 C (700,700) (500,800)

P = $600 D (800,500) (600,600)

S = $500

N = 3: (pollution = $100 to all, filter = $200):

C,C,C = (800,800,800)

C,C,D = (700,700,900) (symmetric)

C,D,D = (600,800,800) (symmetric)

D,D,D = (700,700,700)

You can see that, even in a three player game, each person knows that if at least one person defects, it is in their best interest to defect too. This will result in an all-defect situation. But they also all know that they would all be better off in an all-cooperate situation than an all-defect situation. So it would behoove them to figure out how to make such an arrangement if this possibility and all-defect are the only two stable attractors.

The proposition that N-player Prisoner Dilemmas always result in stable all-defect scenarios is not quite true - it is only true if no party is capable of considering forming a cooperative coalition with the others. In the final analysis, the incentive still exists for all the players to find a cooperative agreement.

"Always defect" is actually one of the simplest strategies, so we would expect it to appear sooner in the list of available strategies to consider. Cooperation often seems more complicated - and yet for a true prisoner's dilemma, cooperation has to be net higher sum than some combination of defection and cooperation.

Defect is the “fallback” strategy. Anyone can individually decide to defect at any time, when everything else fails. Cooperation is technologically advanced, and a structure that has to be built via successful communication with others. The structure can be damaged and collapse.

Contra Thesis / Steelman: The "Goddess of Everything Else" is a good metaphor, if it's actually referring to ever-increasing scope and decreasing locality. E.g., one-shot going to iterated, n-shot going to infinite or indefinite, simple strategies to complicated ones (like neural networks and so on), parameters in the equations going from fixed to variable, emergence of unknown unknowns, and on the most meta-level, anything we haven't thought of yet.

The tragedy of the commons is not so hard to solve. In fact, the first female awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics discovered that communities were actually capable of preventing the depletion of scarce resources without either state intervention or markets, studying farmers, fishers, and foresters. 2

Examples From Compass Rose

Critique of Paul Graham / Y-Combinator

But something must be missing from the theory, because what Paul Graham did with his life was start Y Combinator, the apex predator of the real-life Stanford Marshmallow Prison Experiment. Or it's just false advertising.

Ben Hoffman suggests YC is primarily concerned with perpetuating its brand and network effects rather than identifying or supporting truly innovative startups. He accuses YC of fostering a culture where startups are rewarded for gaming growth metrics rather than building sustainable or genuinely valuable products.

He appears to accuse Paul Graham of being hypocritical:

In fact, Graham's behavior as an investor has perpetuated and continues to perpetuate exactly the problem he describes in the essay. Graham is not behaving exceptionally poorly here - he got rich by doing better than the norm on this dimension - except by persuasively advertising himself as the Real Thing, confusing those looking for the actual real thing.

Just as a quick sanity check, Google still says that Y-Combinator is one of the most successful VC firms in the world, with significantly higher returns than average (feel free to check me on this). For this fact to be simultaneously true with Hoffman’s thesis, we would need a lot more of society to be following these same rules. Most of capitalism would have to be built on a ground of fakeness and unreality.

Hoffman quotes Sam Altman in an interview with Tyler Cowen:

If you look at most successful founders, they are pretty smart, upper-middle-class people. They are very rarely the children of super successful people. They are very rarely born in real poverty. They are very rarely the absolute smartest people who otherwise would win a Fields Medal. They are never dumb, but upper-middle-class, pretty smart people that have grit and drive and creativity and vision and edge and a different way of thinking about the world. That is what I think I’m good at spotting, and that is what I think are good founders.

And Hoffman’s reply to this is:

In other words, the people who best succeed at Y Combinator's screening process are exactly the people you'd expect to score highest at Desire To Pass Tests.

It’s hard not to interpret this as hyperbole — and yet, the negativity is one aspect we can discern to be sincere. So, Hoffman’s basic problem is that Altman selects for well-rounded people who are at least smart enough, but not purely on IQ? Isn’t he doing exactly what he’s supposed to do, by not Goodharting on a single metric!?

Here’s something Paul Graham believes about being evil and how that relates to success:

So let’s take the following things as assumptions, here:

Graham says that evil people can’t survive long as tech CEOs.

Graham says that Goodharting metrics is bad practice and doesn’t lead to real success.

Graham himself is very successful.

I think that Hoffman would probably agree with those three assumptions — with maybe the exception of the last one (but it would be an extremely hard debate, with a lot of potential goalpost-moving). If Hoffman believes all three, then he is criticizing Graham for hypocrisy — essentially that he must be lying about what he actually believes. This is the most reality-critiquing stance. If he believes only the first two, then he is saying Y-combinator is unsuccessful because it does exactly the opposite of what its founders say they believe.

But Y-combinator is not unsuccessful.

Therefore I believe that Y-combinator is doing what its founders believe it’s doing.

Note that its founders are not reality-critiquing.

How Great is Baudrillard, Actually?

This has obtained some memetic status in the rationality egregore:

Baudrillard, author of "Simulacra and Simulation", claimed that "The Gulf War Did Not Take Place." By this, he appeared to mean that the "Gulf War" in the sense of the information that Americans received about the war via the media in fact displayed something that was purely theatrical. The "televised" version of the Gulf War was in fact a simulation that was designed to entertain viewers.

One could wonder if the Gulf War actually did not take place, or if this is hyperbole of some kind. And if it is hyperbole of some kind, is that because Baudrillard himself is trying to operate using his model? But if so, this also makes one wonder how to adjust for this. How much did or did not the Gulf War actually take place? At a certain point, you have to actually know the truth. It could be that the truth is obtained from first trying to reason about what a "real war" would actually look like, and then comparing this to what was shown on television. Where did Baudrillard get his prior knowledge about wars from?

Baudrillard's central point was that these constructed realities can become more important to us than the "original" referents.

Dawkins' Theory of Memetics vs. Baudrillard

Richard Dawkins argued that "memes" are cultural units of information akin to genes that also propagate and spread in similar ways. They are also subject to the same evolutionary pressures as genes. One can think of both genes and memes somewhat like "packages" that contain many things at once, and offer positive or negative total benefit possibly via the influence of only a subset of parts. In the same way that the utility of genes offered to an organism increases the probability that genes will be replicated and passed down to subsequent generations, memes are also evaluated by their pragmatic utility to the bearer (one might say "believer" or "transmitter") of the meme, which in turn increases the probability that the meme will be subsequently transmitted and spread. (See Scott Alexander's recent pieces on the rise of Christianity).

Framing Baudrillard in terms of Dawkinsian memetics, Baudrillard's theory of simulacra, "The Gulf War" (presented to the public), and "The Gulf War Did Not Take Place", are examples of memes themselves. Baudrillard could therefore be interpreted as arguing that "The Gulf War" (presented to the public) had stronger memetic fitness than "The Gulf War Did Not Take Place", the latter of which is also presented as being the truth. If one accepts the prior assumption that "The Gulf War Did Not Take Place" is a more accurate telling of history than "The Gulf War" (presented to the public), then one would be reasonably expected to infer that perhaps the latter obtains more memetic fitness from its relative lack of accuracy, somehow.

It's important to note too that the collection of essays "The Gulf War Did Not Take Place" is not politically neutral, in that it makes value propositions on the nature of the Gulf War itself, claiming that while it did indeed take place, it was not a war but an "atrocity." For what it’s worth, I only make a neutral value judgement on the mere fact that Baudrillard’s essays are not neutral, as I consider that to be the default and natural situation.

It's time to state what my opinion is here: It's very important to note the political nature of certain memes such as these, that show visible signs of making value propositions against another value proposition which can be inferred to have been made by an opposing side, which will certainly be the case here because of the subject matter of war. In a situation where there exists a "Tribe A" (with its associated memetic package) and a "Tribe B" (with its associated memetic package), where Tribe A and Tribe B have competing or adversarial value propositions, it is very straightforward to see that it is not guaranteed for the relative balance of power to remain the same. So without loss of generality, assume Tribe A gradually appears to witness more success and growth. Then, if a member of Tribe B witnesses this as well, and they have also accepted their memetic package as being "true" (which it likely claims to be), it would appear to the member of Tribe B that "truth is losing the memetic war", so-to-speak.

I hesitate to state the obvious, which is that an outside-view perspective might conclude that Tribe A's total memetic fitness is higher than Tribe B's, and so that the probability of a random statement's truth sampled from Tribe A is likely higher than the same from Tribe B.

Judgment, Punishment, and the Information-Suppression Field

Not explicitly Baudrillardian, but I didn’t want to leave this one out.

In this piece, Hoffman argues that there is a specific dynamic - centered around perceived judgmental behavior - that creates an “information suppression field.”

For example, people who mislead others - say by promoting homeopathy - have an advantage against critical truth-tellers, who would be perceived as overly judgmental if they were to voice criticisms.

One important characteristic of this setup is that it structurally advantages information-suppression tactics over clarity-creation tactics.

If I try to judge people adversely for giving me misleading information, I end up complaining a lot, and quickly acquire a reputation for being judgmental and therefore unsafe. Ironically, I get more of the behavior I punish, since being categorized as judgy leads to people avoiding all vulnerable behaviors around me, not just the ones I specifically punished. I cut myself off from a lot of very important information, and in exchange, maybe slightly improve the average punishment function - but this would provide an information subsidy to all other judgy agents, even ones whose interests conflict with mine and are trying to prevent me from learning some things. And most likely I just add to the morass of learned inhibitions.

There is something I am confused about here, namely, what actually creates what appears to me as a noticeable asymmetry.

For example, any behavior is open to punishment, and any punishment could be fine-turned for severity and applicability to different scenarios. Any act of punishment could be judged negatively or positively (these negative judgements themselves punishments), and these acts of punishment could be done in any manner of openness or secrecy. Any judgement could be questioned for social proof before it becomes accepted as common knowledge.

Note how he says “and quickly acquire a reputation for being judgmental.” I would ask the obvious: why did this happen so quickly for you? Don’t you have to be judged as judgmental?

He also says, “being categorized as judgy leads to people avoiding all vulnerable behaviors around me” — why would that be? Why does this asymmetrically not occur for the deceptive (or at least an overconfident, lower-quality thinking) person, who would have had to behave judgmentally to you? Why did you feel unable to retaliate in a tit-for-tat or win-stay, lose-shift kind of manner?

I almost hesitate to ask, but: Is it something like a cultural dichotomy between “being nice” and “being an asshole”, where the latter feels free to engage in unrestricted warfare, but the former feels tied down by numerous moral strictures? Perhaps that excessively modest people are more easily persuaded to keep quiet?

To be sure, this is why I have been motivated to advocate for “more assertiveness, more self-un-gaslighting, more willingness to act unilaterally for morally noble purposes in group settings”, etc.. But clearly, this is not actually an issue of what the true incentives are, but rather a setting in which people basically possess inferior information about which strategies are wisest to follow, even in short time horizons.

Examples From Sarah Constantin

Is Stupidity Strength?

This seems like a good place to actually gauge the community’s general level of reality-critiquing versus system-critiquing.

I expected before, and generally have judged after reading, that Constantin - like either of the two previously discussed authors - is not purely reality critiquing (but also probably can’t be, as I mentioned before). Even still, there are some nuances here that I think ought to be be analyzed.

The point is, irrationality is not an individual strategy but a collective one. Being bad at thinking, if you're the only one, is bad for you. Being bad at thinking in a coordinated way with a critical mass of others, who are bad at thinking in the same way, can be good for you relative to other strategies. How does this work? If the coalition of Stupids are taking an aggressive strategy that preys on the production of Non-Stupids, this can lead to "too big to fail" dynamics that work out in the Stupids' favor.

Here we have again that malignant dynamics are a product of society, not the individual. If the “stupids” (who are far larger in number than the “smarts”) figure out a way to coordinate, they can overpower the “smarts” and force them to act stupidly too.

She mentions Theodore Roosevelt as a proponent of the dichotomy between thinking versus doing. I like Teddy Roosevelt, and I’m a nerd, so let’s look at the particular quote she’s referencing:

Let those who have, keep, let those who have not, strive to attain, a high standard of cultivation and scholarship. Yet let us remember that these stand second to certain other things. There is need of a sound body, and even more need of a sound mind. But above mind and above body stands character—the sum of those qualities which we mean when we speak of a man's force and courage, of his good faith and sense of honor. I believe in exercise for the body, always provided that we keep in mind that physical development is a means and not an end. I believe, of course, in giving to all the people a good education. But the education must contain much besides book learning in order to be really good. We must ever remember that no keenness and subtleness of intellect, no polish, no cleverness, in any way make up for the lack of the great solid qualities. Self-restraint, self-mastery, common sense, the power of accepting individual responsibility and yet of acting in conjunction with others, courage and resolution—these are the qualities which mark a masterful people.

This reminds me a lot of what Sam Altman said about the founders he looks for, that “they are never dumb, but upper-middle-class, pretty smart people that have grit and drive and creativity and vision and edge […]”

To me this reads as more of a (literally pragmatist) view of how people should be well-rounded and include the full measure of good qualities, and not necessarily against intelligence, nor that intelligence and (other characteristics) should be treated as separate magisteria with trade-off-like qualities.

I’m a bit uneasy with rejecting pragmatism too much, and I think the claim that it is anti-intellectual is a bit of a motte-and-bailey. Clearly, it explicitly rejects basically nothing.

The Pragmatists were not rejecting intelligence - nor do I actually think that people like, e.g., Trump are. I think Trump playing to people’s emotions could be a wise strategy, especially if there happened to be another political party which implicitly seemed to reject them. I’m not saying this must be the case.

There are two options to consider in regards to Pragmatism:

It correlates with truth perfectly anyway, and is therefore a better heuristic for actually measuring truth. In this case we don’t have to worry.

It doesn’t correlate perfectly with truth. However, genuinely following an empirical and consequentialist utility-maximizing strategy is still (basically by definition) better. Therefore we re-evaluate what we consider ‘true’ or even what we consider to be the definition of ‘truth.’ If we valued ‘truth’ high enough to be worried, then we re-evaluate the consistency of our values (still falling under pragmatism).

In the last post in this series, we come to a concrete example: venture capital. Is venture capital that bad? Financially, not really. However, they are biased towards chads:

I'm claiming that there is a lot of "dumb money" out there, which favors handsome, masculine men even when they lose money.

Gary Becker's theory about prejudice was that it ought to eventually die out. racist employers who won't hire black people will eventually go out of business in a competitive market; any irrational prejudice in business owners or investors, should be selected against relative to optimal profit-maximizing behavior. If we see persistent prejudice that goes against financial self interest, the market must be non-competitive.

Well, we see persistent prejudice in investment! In the most obvious way you'd expect: bias towards traits that make people high-status in our society. People spend money on people who look like winners; they don't check track records of actual winning. Why don't they all go broke and thus remove themselves from the market? I don't know, but they don't.

So, that’s it, huh? Society has a bias towards handsome chads, that doesn’t go away.

At least at the very end, she makes a prediction that such stupid coalitions should lead to “market crashes.”

Maybe not so dramatic, but if being intelligent and not a handsome chad outperforms being intelligent and a handsome chad in the marketplace, we should eventually start to see that earn some gradual dominance.

A System Critique of Reality Critique

Taking PR Literally Is Reality-Critiquing

In this post, I analyzed conflict and mistake theory, pointing out that these are two possible frames between two adversarial parties. One of which (the aggressor) frames the other party as having made mistakes (which itself could be framed as an act of aggression, but this is assumed to be implicitly deceptive). The aggressor typically sees the situation as zero-sum as well as rationalizes their aggression as unavoidable. The way that the aggressor manages PR is what ultimately produces the two diverging frames.

As I've alluded to throughout this post, there are two major frames for analyzing societal failures:

Caused by (unwise) zero-sum, conflict-oriented thinking, as well as other general mistakes in cognition.

Caused by (wise) savvy thinking, but where conflict is unavoidable.

The second one is the PR-friendly frame. Therefore, when failures do occur, we expect to hear the second frame disproportionately more than we expect it is honestly believed to be the cause. The second frame, furthermore, is self-recommending.

"Conflict is unavoidable" is very likely to be something believed by someone more prone to conflict-oriented thinking.

Cynicism is Self-Recommending

Circular motivations as calls-to-action:

Everything is "high stakes."

Progress continues equivalently on X axis but differentially on Y. This is back-chained to be the cause of the "hinge."

X is most often things like "capability", Y "values."

Because "values" are the things tribes rally around, Y is sometimes equated with non-CEV human values like religion and culture, including politics.

Hard to act on pure complaint - but a complaint self-argues as being “pivotal” while also reinforcing the belief.

Cynicism is self-arguing:

The game is rigged! We are forced to play by the rules of the rigged game!

Conveniently, this means we can be really “low-effort” (basically, by complaining and being in-groupy) if we want to.

Moloch / the game theory “folk theorem” says that bad equilibria are stronger the more everyone believes in the bad equilibria!

Therefore, too much "Oh no, Moloch!" is Moloch.

All of this implies that reality-critique is not actually adaptive at all, but rather a maladaptive worldview that is constructed via circular reasoning.

It seems very well tailor-made for “scenes” and movements, because all of the above can be performed socially.

If you happen to be in such a scene, then any instance of “zero sum” behavior can be argued to be an insidious local optimum - possibly therefore being unavoidable to any of the participants. The more that this belief gets reinforced, the more plausibly true it actually becomes.

I think this differs from Baudrillard in that it requires the “scene” in which it takes place to be a little bit extra ungrounded from reality beforehand (so that everything inside of it can be completely self-arguing).

However, I think that this situation is far more unstable than is typically given credit for. Pessimistic, postmodern-influenced movements still have no choice but to act in the social environment they are embedded in as well, not just their own. They still have to produce their own propaganda and garner enough material and financial support to survive.

They are by no means guaranteed to perform well if push comes to shove with any other groups outside of it. Any other group hostile towards this group could use the strategy of pointing out instances of circular, self-referential reasoning, not to mention the many instances of truth-suppression or judgmentality that would be required to prop up such a brittle structure.

There are ways I believe one can lower the stakes of anything they do inside either organizations or movements, and it is not necessarily the case that Moloch, or any other negative, self-reinforcing social dynamics, actually are overpowering enough to make applying pressure against them inadvisable. I recommend being steadfast and developing personal “Exit” — the ability to freely leave and join social structures at will, as much as possible.

The “effective accelerationists” might be trying to do something like this, however.